Why I made MD-SAPT

Alia Lescoulie

February 4, 2024

MD-SAPT: A Mixed Methods Approach to Analyzing Protein Interactions

What is MD-SAPT

MD-SAPT is a piece of Python-based software for analysing the interactions of simulated proteins using quantum mechanics. This is an approach that mixes the two methods for modeling chemical systems, classical and quantum. Neither method is better than the other, they just play different roles.

Classical physics based models, such as molecular dynamics (MD), simulate atoms at point masses and bonds as springs, allowing for dynamic models that simulate the motion of a system over time. These models can efficiently simulate hundreds or thousands of atoms, offering a way to model the dynamics of proteins in water or lipid bilayers. A major limitation is their accuracy for specific interactions, since they approximate the effects of electrons away as standardized parameters, they can only model intermolecular interactions to within a few kcal/mole.

Quantum physics based methods model a molecule as a collection of wave functions that describe the behavior of each of its electrons. These models are very computationally intensive, with complexity scaling exponentially with the number of electrons, making them impractical for systems large systems. Despite the computational demands, quantum calculations for intermolecular interaction are accurate to a tenth of a kcal/mole.

MD-SAPT allows scientists to run quantum calculation on their MD simulation data so that they can get more accurate data about interactions in the proteins they’re studying. This is potentially useful for drug design, where the difference in interaction energy between one potential drug and another could easily fall into the margin of error using MD alone.

What Lead to MD-SAPT

The idea for MD-SAPT’s mixed methods approach emerged from previous research in the group analyzing active site interactions within molecular dynamics (MD) data. Previously our group preformed MD simulations the protein MEK1, a dual-factor human kinase responsible for cell cycle regulation, and potential target for chemotherapeutics (see this paper for more info). That work identified key amino acids in the protein responsible responsible for binding with ATP, and continuing the cellular replication process. We decided to use a quantum method called Symmetry Adapted Perturbation Theory (SAPT), which quantifies the interaction energy by determining the contribution of the different types of intermolecular interactions. This not only gives a very accurate result for intermolecular interaction energy, but also quantifies how the interaction is occurring ie (interaction between charged atoms). Running SAPT calculations from on data from protein MD simulations requires several steps, and must be preformed repeatedly:

- Pulling coordinates for the selected amino acid residues or ligands (small molecules that bind to a protein) from the MD simulation

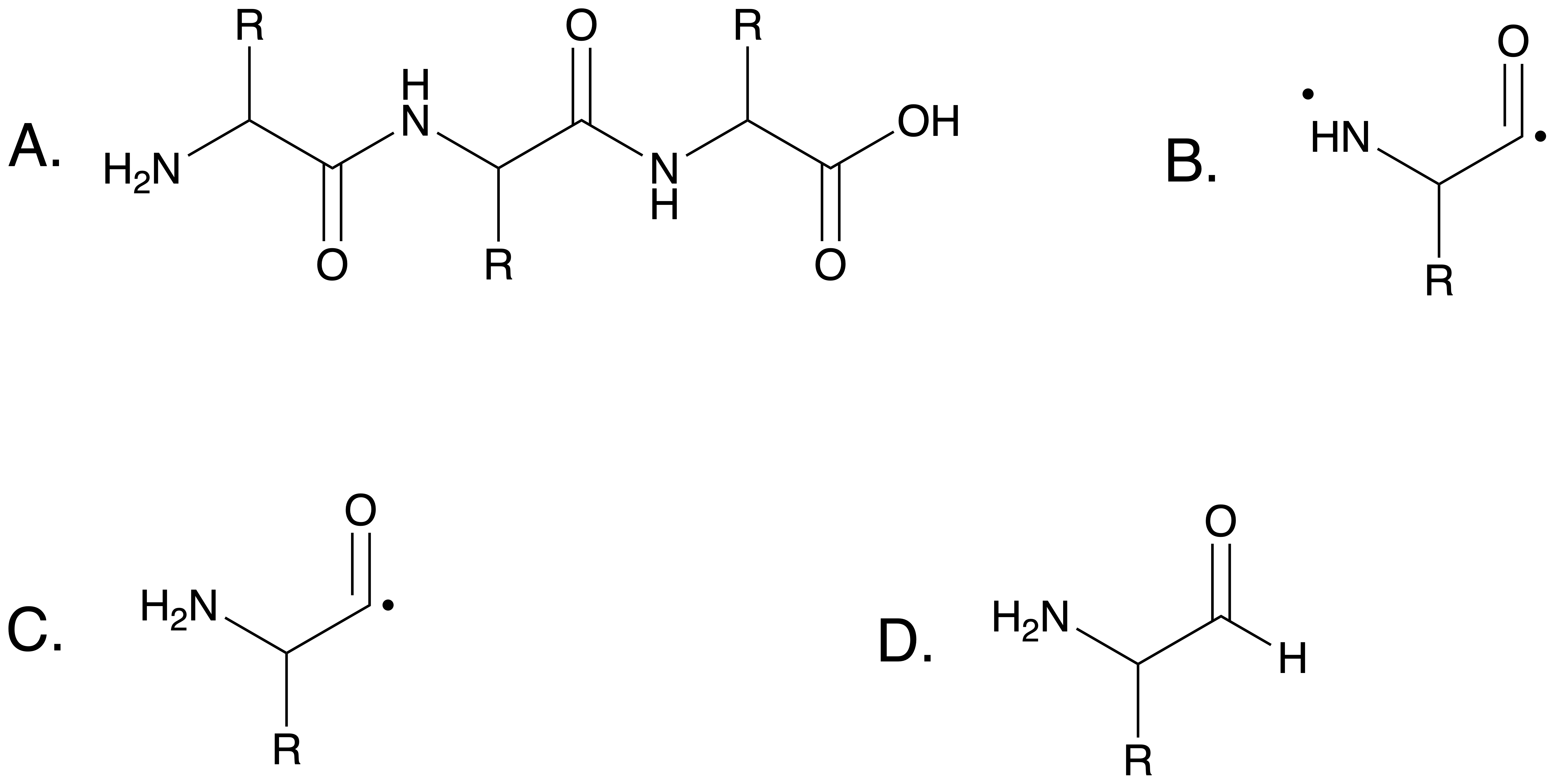

- Modifying the selected molecules so that there aren’t any unpaired (radical) electrons. This is a problem because when the residues are separated from the protein chain it severs bonds leaving behind lone electrons

- Determining the charge and spin state of each molecule for the SAPT calculation

- Passing the correctly formatted molecular coordinates into Psi4 to run the SAPT calculation

Previous members of the group spent several months attempting to run SAPT calculations on the MEK1 data manually, but the process was slow, error prone, and very tedious. In addition the SAPT calculations failed frequently, likely due to leaving radical electrons on the analyzed residues. After the project was passed to me in early 2021, I read over the details and thought I could make a tool to solve this process with a Python program using the Psi4 API. This idea took a backseat to research work my very large courseload in spring 2021 until that fall.

MD-SAPT was started late summer of 2021 after my internship at Arizona State University in Oliver Beckstein’s computational biophysics group. During the internship I learned a great deal both about the fundamentals of software engineering and how to develop in the open-source Python ecosystem. That internship taught me how to take what I had learned up to that point in two quarters of computer science and apply it to actually building software that solves problems for real users. Those skills were what enabled me to start MD-SAPT, which went on to define my work in the Computational Chemistry Group over the subsequent years of college.

I continued developing MD-SAPT throughout that fall quarter and had an alpha version done in early January 2022 after a very productive winter break. A surprising amount of my breakthroughs on this project occurred during the 2 hour Amtrak layover in Hanford, a small city in central California, when traveling between San Luis Obispo and my hometown Fresno. I don’t know what it is about that Starbucks near the train station in Hanford, but I got so much code written there over the 3 years of taking Amtrak between my hometown and college town. I certainly don’t miss the fact that it took the better part of a day to travel a distance that takes 2.5 hours by car, but the trips certainly were productive.

MD-SAPT improved significantly over the next year. That January I brought on my girlfriend (at that time of less than 2 months) Astrid to work on devops for the project. Having someone with actual production engineering experience meant that I could focus on features, and writing up my work. Bringing her on was an excellent decision since she could do continuous integration and deployment in a fraction of the time it was taking me.

In the future I’ll write an post about the code works in more detail, for information on how to use MD-SAPT you can look at the readthedocs page.

Future Directions

Currently the biggest limitation of MD-SAPT is that it only supports MD simulations of proteins. MD is used for all kinds of molecules including other biomolecules like nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) and lipids, its also used to study polymers used in plastics and other manufactured materials. The reason for this limitation is simple, when pulling a monomer out of polymer chain, you are severing the bonds between it and its neighboring monomers, leaving atoms with an odd number of electrons (see above image). Not only does this inaccurately represent the electronic structure of that molecule, it often causes errors in SAPT calculations. MD-SAPT currently has code for replacing the missing bonds in amino acids, but I’d like to provide a way do the same process for nucleic acids. MD-SAPT doesn’t offer a repair function that generalizes the process since the bond length for the new atoms, and even which atoms to use is specific to the molecule being analyzed. Additionally I’d like to implement a system for users to write their own functions to repair bonds for their particular use cases, and specify which repair function to use on each molecule being analyzed. This would allow users to analyze MD simulation on any type of polymer using MD-SAPT, and only have to provide a few of their own function instead of replicating the whole workflow.